There was a Tuesday evening library visit a few weeks ago that I didn’t write about. I found a slim volume, a collection of papers delivered at the ICA in London, Ideas from France; the Legacy of French Theory, edited by Lisa Appignanesi (1985). The book has four sections: The Pleasures and Pitfalls of Theory; The Archeology of Michel Foucault; The Rise and Fall of Structural Marxism; The Uses of History. I chose to read around in section two, the one on Foucault. In “Foucault & Psychoanalysis,” pp.24-26, John Forrester wants to know what Foucault’s relation to psychoanalysis was. He notes that while La volont� de savoir purports to be an archaeology of psychoanalysis, “there was something too neat about the project: if the book were the archaeology of psychoanalysis, why was there so little textual reference, so little explicit addressing themes in psychoanalysis? To me, it seemed clear that many arguments were implicitly aimed at psychoanalysis (amongst other things). Yet sometimes the other things were so vaguely evoked, so tangential, while the unnamed object was so obviously pshychoanalytic [sic] that I felt that there was something odd, refracted and displaced about the book.” (25) Forrester eventually discusses

There was a Tuesday evening library visit a few weeks ago that I didn’t write about. I found a slim volume, a collection of papers delivered at the ICA in London, Ideas from France; the Legacy of French Theory, edited by Lisa Appignanesi (1985). The book has four sections: The Pleasures and Pitfalls of Theory; The Archeology of Michel Foucault; The Rise and Fall of Structural Marxism; The Uses of History. I chose to read around in section two, the one on Foucault. In “Foucault & Psychoanalysis,” pp.24-26, John Forrester wants to know what Foucault’s relation to psychoanalysis was. He notes that while La volont� de savoir purports to be an archaeology of psychoanalysis, “there was something too neat about the project: if the book were the archaeology of psychoanalysis, why was there so little textual reference, so little explicit addressing themes in psychoanalysis? To me, it seemed clear that many arguments were implicitly aimed at psychoanalysis (amongst other things). Yet sometimes the other things were so vaguely evoked, so tangential, while the unnamed object was so obviously pshychoanalytic [sic] that I felt that there was something odd, refracted and displaced about the book.” (25) Forrester eventually discusses

“an early work of Foucault’s, one that I have never seen discussed. Perhaps it is Foucault’s earliest publication: the Introduction to a French translation of Ludwig Binswanger’s Traum und Existenz. (…)

According to Foucault, the dream as analysed by Freud gains access to the meaning of the unconscious — it is a semantic analysis. But it leaves out of account the morphology of the imaginary:There is a different morphology of imaginary space when what is at issue is free, light-filled space, or when the space at work is that of the prison of obscurity and of suffocation. The imaginary world has its own laws, its specific structures — the image is a bit more than the immediate fulfilment of meaning; it has its own density, and the laws of the world are not solely the decrees of a single will, were that one divine.

It is also clear that Foucault’s reading of Freud was already influenced by Lacan, as every recent French writer on psychoanalysis has been; but this is the Lacan of 1954, the Lacan of a metaphysics of full speech, of the necessarily deceptive functions of the imaginary. [Pay attention, next comes the bit that interested me from an art historian’s p.o.v.:] Foucault resisted this metaphysics of speech. He opposed Klein and Lacan, and opposed them to each other, with the independent logic of the image, resistant to the linguistic interpretation, the speech-ocentrism, if you will allow me to say that, of psychoanalysis. Hence Foucault’s interpretation of Dora sees her cure as effective, because the dream in which she announces the termination of the treatment maps out her struggle to escape from the interpretive strategies of Freud and all the others with whom she is in everyday contact, both men and women. It announces her means of escape from the iron law of Freud’s theory of identification, in which every image of herself and of the others is just a representation, and a representation of something else. For Foucault, Dora becomes heroically, stoically cured through acknowledging her solitary destiny, by walking out on Freud. If she were to say it, she would only be subjected (in all the senses of the term) to Freud’s steamrollering interpretive strategies. Dora’s truth cannot be found along the path of psychoanalysis because the communication of psychoanalysis will leave the expressive force of the image untouched and will attempt to dispel it, since psychoanalysis is wholly committed to an analysis of representation, rather than expression. What is more, her truth will only be found by the solitary escape from the prison of representation.” [emphasis added]

Next, Peter Dews compares “Foucault and the Frankfurt School,” 26-28. By Foucault’s own admission, he could have been twenty years further along had he discovered the Frankfurt School sooner. Dews writes, “‘It is a strange case,’ he [Foucault] states, ‘of non-penetration between two very similar types of thinking which is explained, perhaps, by that very similarity.'” I love Foucault’s take here: I see him and the Frankfurt School making lesbian love. It should indeed have happened. The way I understand Adorno, the problem of violence was central to his thinking. Adorno tried to articulate a “negative” dialectic, a philosophy that wouldn’t be a philosophy, a language that would eschew the regulating force of language, its violence, and its conformity. Dews elaborates as follows:

…the work of Foucault and of the Frankfurt School is haunted by the idea of a “utopia” of nonregulated seriousness [i.e., play]. In The History of Sexuality, for example, Foucault permits himself to evoke fleetingly a “different economy of bodies and pleasures” which would no longer be subordinate to the confessional quest for identity, while in Negative Dialectics Adorno argues that “all happpiness aims at sensual fulfilment and obtains its objectivity in that fulfilment. A happiness blocked off from every such aspect is no happiness.”

Note that in History of Sexuality Foucault made the case that psychoanalysis is not a “major break in knowledge” but is instead yet another way of making sex discursive (i.e., something talked about). Foucault’s point was that “sexual liberation” — as manifested in open discussions about sex — is in reality an extension of systems of power and domination that have infiltrated our most private activities. In other words, the more you bring activities previously considered non-verbal under the control of language, the more you’re extending mechanisms of social control into those areas. (That’s why I think you have to be a nitwit to praise pornography, because even though porn is visual, it is a visual mode cliched into language patterns, it is prepackaged narrative, it is a form of spectacularism avidly trying to shed its spectacularity and slip instead into the norms of language. It is in that sense a new form of “global” control, and hardly one of “global sexualisation,” whatever that’s supposed to be.) You can talk yourself silly about sexuality; just remember that it’s not called the prison-house of language for nothing. And that’s what I was reading about a couple of Tuesdays ago.

{ 7 comments }

A brilliant post … especially in the light of your next post, which, even though grapples with the issue of the embodiment of blogs, is revealing of the “negative dialectic” that may well be at work in blogging.

Yule, just wanted to let you know that your writings that bring a deep tradition of theory to the analysis of the cultural beat of blogs has been a gift of the blogosphere.

But, more to the point of this post: What a great response to that “sexual globalization” post that hails the gale force winds of sexual culture (not realizing the oxymoronic coupling of sexual and culture in the phrase itself!) as some kind of great liberating army that marches across monitors from Osaka to Abu Dhabi, when if fact, it’s the pied piper of Hamlin whose come to claim the children…

You are right, much of that post read as paean to pornography and the idea that cultural divesrity somehow has the power to redeem pornography!

Thanks for the kind words, Maria. I try to come at things obliquely. It’s a luxury of blogging to be able to post impressionistic writing, something that isn’t completely set in stone. I couldn’t begin to find the time to marshal all my arguments against the globalisers, but I can find enough energy to point at stuff that criticises the simple-mindedness of uncritical affirmation. Hey-ho, and so it goes. Maybe we’re doomed as a species, who knows.

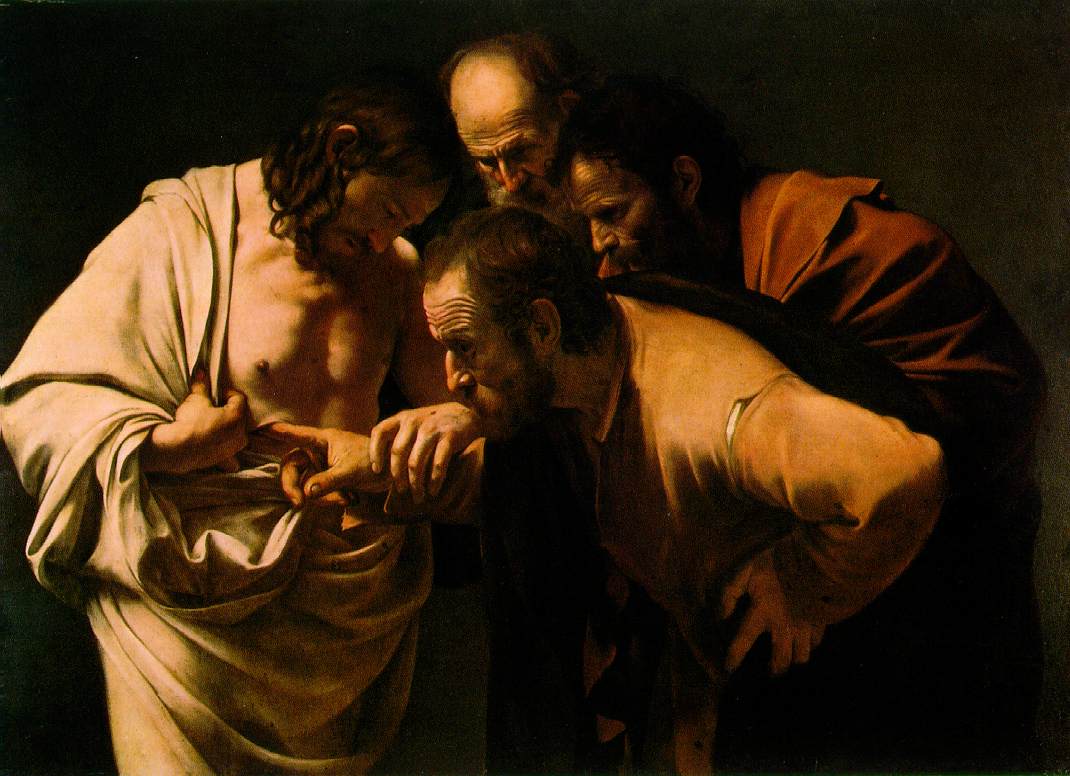

And although I’m not a Christian, I couldn’t resist consoling myself with that picture by Caravaggio of the doubting Thomas getting a materialist and visual lesson in reality. I totally adore Caravaggio — he was one of the very best painters, ever. …So much to learn from Caravaggio, so much.

Well done. This blog post is well-worded/hilarious. “… [Foucault] and the Frankfurt School making lesbian love.” Who would’ve thought. Anyway, I ended up at your blog via Google surprise surprise. I was looking for a reference in this purple paperback, *Technologies of the Self,* and couldn’t find it, so I searched Google using the key terms “Foucault” and “utopia.” Though I didn’t exactly find what I was looking for, I’m glad I ended up here instead. Your writing is an enjoyable read. Also, great take on pornography and Caravaggio is the man. Peace.

Well done. This blog post is well-worded/hilarious. “… [Foucault] and the Frankfurt School making lesbian love.” Who would’ve thought. Anyway, I ended up at your blog via Google surprise surprise. I was looking for a reference in this purple paperback, *Technologies of the Self,* and couldn’t find it, so I searched Google using the key terms “Foucault” and “utopia.” Though I didn’t exactly find what I was looking for, I’m glad I ended up here instead. Your writing is an enjoyable read. Also, great take on pornography and Caravaggio is the man. Peace.

That purple paperback you mentioned looks interesting, Tara. I first thought you meant Technologies of Gender (by Teresa de Lauretis), but then saw that it’s not purple. So then I thought, maybe she means The Self and Its Pleasures (by Carolyn J. Dean), which is purple-covered. (I have both those books, although it’s been a couple of centuries since I read them.) Then I realised, “no, d’oh, check Amazon,” and indeed, you did mean Technologies of the Self. But since I’m at it, I’d also recommend Reconstructing Individualism (ed. by Heller, Sosna, and Wellbery).

Of course now I’m curious as to what reference in that purple paperback you were looking for…

Thanks for commenting!

Just to sate your curiosity, it’s funny actually, I was looking up a reference to comment on another blog–which was utterly random and incoherent in comparison to yours, so I ditched that endeavor. But the reference had to do with the danger of utopias and systematic thinking, basic stuff but brilliantly worded. It’s found in a Foucault interview with Lotringer (I’m pretty sure) at the beginning of the book, or within his “Technologies of the Self” essay. Though now you have me thinking of all the intriguing purple-colored books I’ve ever read. There’s one by Foucault and Blanchot (Zone Press) I think, but it’s mostly black; it has splashes of purple. Anyway, thanks for replying and the reading recommendations.

Comments on this entry are closed.